Some Wine with that Cheese? The Work of Professor Izumi Fukunaga

To understand Izumi Fukunaga’s work, it helps to appreciate a glass of red wine with cheese. Imagine the way a certain vintage is offset by a blue cheese versus a camembert, for instance. This, more or less, is what Fukunaga and her team do in the lab.

Of course, the researchers do not get to attend wine tastings. They use odorants—lab-made chemicals that simulate the role of cheese and wine—to observe neural function in mice.

“Do you know that book Where’s Waldo,” asks Fukunaga, head of the Sensory and Behavioral Neuroscience Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST). “It’s a bit like that—where you have to find him in the medieval marketplace. There’s a lot of competing signals, and the brain has to sift through them to get the most relevant information.”

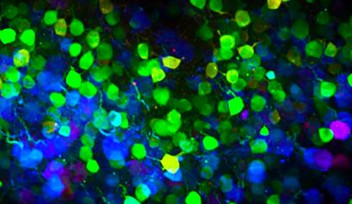

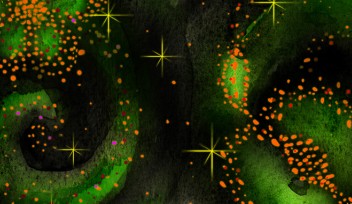

Her team studies how the brain parses incoming signals, blocking out noise in order to focus on the most relevant information—in this case, a particular combination of smells. By imaging the animals’ brains and recording electrical output from particular cells, scientists can describe the neural pathways the animals use to distinguish one experience from another.

Fukunaga’s group—which has grown from just her to a fully fledged unit over the past year or so—studies inhibitory neurons, which are key to understanding how the brain processes information. They look at interactions between different types of neurons, including specific properties of the connections between them. In doing so, they aim to map the physical pathways inside the brain. Their work has taken shape quickly in the time since Fukunaga arrived at OIST.

“When I met [Fukunaga] this was not even like this,” says Aliya Mari Adefuin, a PhD student at OIST who has worked with Fukunaga for a few terms. Although Adefuin spends most of her time conducting experiments, she recalls a time not too long ago when the lab was empty.

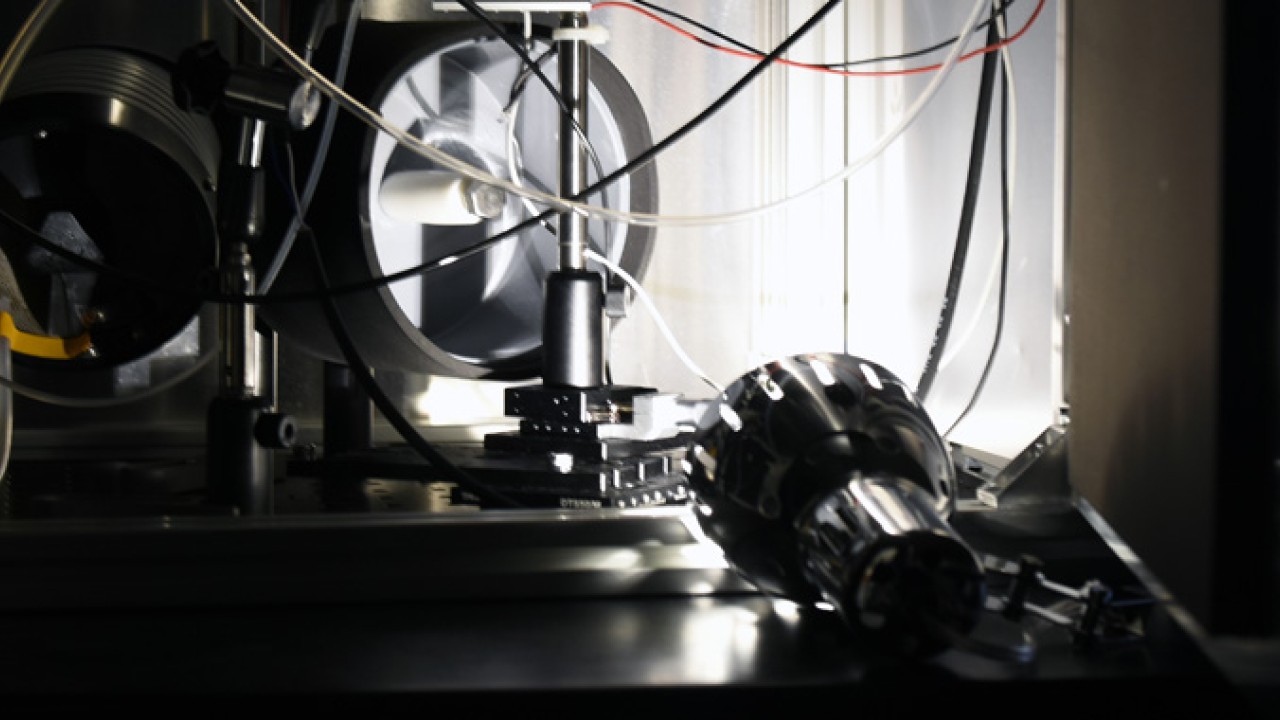

Adefuin gestures around the room, which has heavy black curtains to block off light for areas in which experiments are performed. Beyond the curtains, a custom-designed setup containing a box and dozens of protruding wires and tubes allows researchers to probe what mice are able to do with their sense of smell.

“Making our own equipment gives us so much more flexibility,” she says.

A second room, midway through completion, houses tables with similar configurations, along with microscopes. A powerful infrared laser sits atop a platform. These tools will allow the researchers to study the brain under particular conditions, controlling crucial variables, such as the percentage of the smell solution they use, the number of odorants introduced, and the percentages of each in a combination.

“It’s a work in progress,” Fukunaga says.

Her next task is putting the pieces together, and she looks pleased about it.

Specialties

Research Unit

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form