Surf and Turf: How Land Use in Okinawa Affects the Ocean

According to a recent survey from the Japanese environment ministry, over 70% of coral in the Sekisei lagoon - Japan’s largest reef located between the Okinawan islands of Ishigaki and Iriomote - has died from bleaching. While increasing ocean temperatures are the leading cause of coral bleaching, soil and pollutant runoff from the land also contribute to bleaching events. Interested in how land use affects the reef, Researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) are modeling the amount of soil and pollutant sediment runoff that reaches the ocean, with the aim of being able to estimate the potential damage to surrounding corals.

Corals have a symbiotic relationship with microscopic algae that live inside their tissues. Algae are the primary food source for corals and give them their colour. Environmental stressors such as changes in water temperature, exposure to pollutants, or reductions in sunlight exposure due to suspended soil sediment making the water cloudy, cause algae to leave the coral tissue. Without algae, corals lose their primary source of food, turn white, and are more susceptible to disease. Given the extent of bleaching in Okinawa, it is vital that the remaining corals and related marine ecosystems are protected.

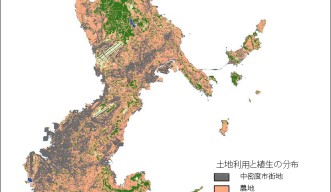

Scientists in OIST’s Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit are using information about the land topography and soil types across Okinawa combined with historical data about the temporal distribution of rainfall and land use over the last 30 years to generate estimates of the amount of sediment runoff reaching the ocean.

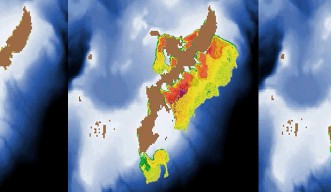

By combining this information with data about sea surface currents, water depth, velocity and direction, the researchers are able to estimate where the sediment flows once it enters the ocean.

This videographic, provided by the Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit, demonstrates sediment runoff during a “typical” rainfall year in Okinawa. Red regions have greater sediment accumulation and green/blue regions have less sediment accumulation.

“We can use the model to study environmental impacts of a single event, such as a typhoon, or over a longer time-scale,” says Kenneth Dudley from the Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit.

Dudley presented the model at a Watershed Management Workshop held at OIST last December, organized by OIST’s Technology Development and Innovation Office. The workshop brought together representatives from the Okinawa Prefectural Government’s Department of Environmental Affairs and Okinawa Prefectural Institute of Health and Environment as well as OIST scientists involved in environmental monitoring, to discuss the problems and potential solutions of sediment runoff.

At the workshop, Supervisory Researcher of the Okinawa Prefectural Institute of Health and Environment, Koichi Kinjo, stressed the urgency of the soil-runoff problem, saying: “We need to implement some counter measures as soon as possible”.

Reflecting on the workshop, Head of OIST’s Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit, Professor Evan Economo commented: “We hope to learn from and coordinate with the Okinawa Prefectural Government and Okinawa Prefectural Institute of Health and Environment. They have been investigating the problem of soil runoff for a long time and we value their expertise in this area. We hope that our research may be useful to them in tackling sediment runoff.”

Research and Development Liaison Officer in OIST’s Technology Development and Innovation Office, Chihiro Tominaga, said: “I hope that by connecting the Okinawa Prefectural Government and OIST researchers, we are establishing a relationship that will flourish in the years to come.”

Still in its early stages, the model may be refined subsequent to further research. For example, exactly where the sediment flows once it reaches the ocean is still unclear and may require more complicated ocean modelling techniques. Further research may also involve validating the model by comparing model estimates to real-life sediment levels in the ocean.

This ongoing modelling research is an important pillar in OIST’s wider environmental monitoring project in Okinawa, The OKEON Chura-mori Project. While Dudley and Dr. Payal Shah have been developing models that show changes in land-use and land-cover in Okinawa over several decades, other researchers have been collecting insect samples and acoustic and video recordings of various animals, with the common goal of monitoring the terrestrial environment of Okinawa.

Homepage image provided by the Okinawa Prefectural Institute of Health and Environment.

Research Unit

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form