From the Pacific to the Atlantic and back again: A (perhaps too) challenging life in science and technology

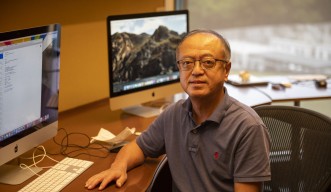

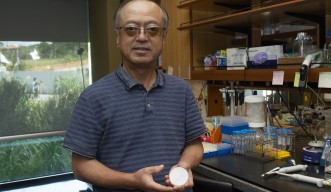

Prof. Ichiro Maruyama has led the Information Processing Biology Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) since 2005. This followed a successful career in cell biology that spanned from Cambridge to California to Singapore. In November 2022, Prof. Maruyama concluded his time at OIST to retire and rejoin his family in San Diego.

As a founding member of four places in four different countries—MRC Molecular Genetics Unit in Cambridge, the Department of Cell Biology of The Scripps Research Institute in Southern California, the Genome Institute of Singapore in Biopolis, and OIST—Prof. Maruyama has challenged many scientific dogmas.

In 1983, Prof. Maruyama was travelling from Tokyo to Heathrow as a Postdoctoral Fellow at MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK. He describes this journey as his first career challenge.

“Just before boarding the flight, a Soviet jet had shot down a Korean airline plane near Hokkaido. Our flight had to be diverted to go through the North Pole, stopping in Alaska. It was more than 20-hours of travel with our 8-month old daughter.”

At MRC, Prof. Maruyama was part of the group that discovered gene amplification in germline cells of a multicellular organism, which is still rare in the field. He worked with Prof. Sydney Brenner, Nobel Laureate and founding father of OIST. Later when Prof. Brenner began the MRC Molecular Genetics Unit in Cambridge, Prof. Maruyama joined him as the only other member.

“I started to buy everything including benches, shelves, and machines. We developed a surface display vector based on bacteriophage lambda for the expression of foreign proteins. We observed single molecules for the first time in history.”

The group cloned and sequenced a very important gene for how neurons communicate. But now, Prof. Maruyama describes the method as messy and says that next-generation sequencing has since replaced it. A notable coauthor on this paper was Ms. Hiroko Maruyama, Prof. Maruyama’s wife. The two collaborate in both science and life.

In 1991, Prof Maruyama made the trans-Atlantic journey to San Diego in southern California. He became a founding member of the Department of Cell Biology at The Scripps Research Institute where he challenged a model for mechanisms underlying the activation of cell surface receptors.

Finally, he made the trans-Pacific journey back to Asia from California. He spent three years at Biopolis in Singapore as a founding member of the Genome Institute of Singapore, then joined OIST, again as a founding member.

“I’d already heard about OIST from Sydney Brenner. Actually, Sydney had asked me if I thought I’d be suitable as a president candidate. I said to him “no, not good, you should be president”. And he accepted. That’s my biggest contribution to OIST.”

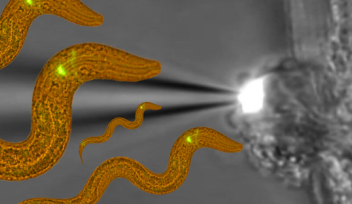

In 2005, Prof. Maruyama began the Information Processing Biology Unit where he looked at how external information, such as environmental change and cell-to-cell communication, is processed at a molecular level. In the last few years, his group has used a number of different models—bacteria, cultured animal cells, a tiny worm called C. elegans. The C. elegans nervous system is very simple, allowing researchers to look more efficiently analyze the processing mechanisms at molecular and cellular levels. The group compares results from C. elegans with those from more complex organisms such as mice. The aim is to contribute to an understanding of mechanisms underlying information processing in human brains. This should, in turn, contribute to an understanding of various human diseases and to the development of drugs for these diseases.

Though now retiring and moving to San Diego, Prof. Maruyama hopes that research collaborations with OIST will continue.

Asked about his advice for early career scientists, Prof. Maruyama answers, “new knowledge is best discovered by young people. Many people say that it’s because students are energetic. But I think it’s actually because they lack knowledge and experience, so they think in their own way. It’s the only way to make major breakthroughs in science. So, I always tell my students to think in their own way, not just by searching through the database or reading books. Also, remember that even experts make mistakes.”

Specialties

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form