The Sound of Music: How the Songbird Learns its Melody

Learning a first language is somewhat effortless. We start learning from our parents before we can even remember and the words and sounds are imprinted in our memory at an early age. Learning a new language as an adult is much more difficult, involves a lot of hard work, and you may never have the same fluency as with your first language. The same is true of songbirds. Zebra finches learn their song when they are young by listening to their father’s or tutor’s song.

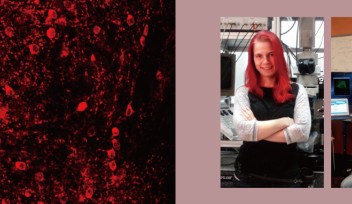

Recently, Prof. Yoko Yazaki-Sugiyama and Dr. Shin Yanagihara from Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) have, for the first time, identified the neurons in the brain that are associated with the auditory memory of the father’s song in zebra finches, which could lead to insight into human speech development. They have recently published their findings in Nature Communications.

“For young animals, the early sensory experiences are very important and strongly affect brain development,” Yanagihara, staff scientist in OIST’s Neuronal Mechanism for Critical Period Unit said. “This stage is called the ‘critical period’ where the brain circuits are very flexible and can be easily changed and modified. We wanted to know how the early sensory experiences during the critical period shape brain circuits and lead to appropriate behaviours.”

In zebra finches, only males learn and sing songs, as this is the way they attract a mate. Therefore, learning a complex song to attract the lady zebra finches is crucial for reproduction. The juvenile zebra finches do this by listening to the father’s song and memorizing it. When they begin to vocalize, it is thought that through their auditory memory of the tutor song they can recall the sounds and gradually adapt their song until they develop their own song, which is comparable to their tutor’s song.

“This is similar to human speech development,” Yanagihara said. “During the critical period children listen to adult speech and their brain circuits are shaped to capture auditory features of that speech. We predicted that when birds listen to father’s song, these experiences modify the juvenile birds’ brain circuits to form a memory of it.”

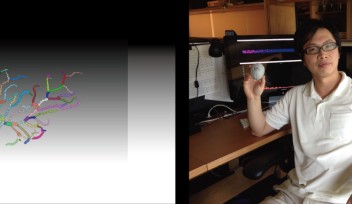

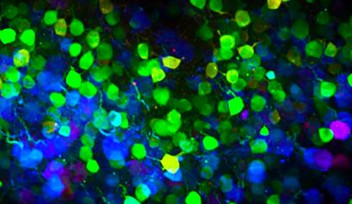

To confirm their prediction and learn more about where the memory of the tutor song is stored, the researchers looked at the response of neurons in the higher auditory cortex – which is a part of the specialized neural circuit – to the sound of the tutor song. They monitored the neuronal auditory response when the birds listened to different songs –their own, the tutor, other zebra finches, and the songs of different songbird species – in tutored juvenile birds and in isolated juvenile control birds.

The team monitored responses in single neurons and collected information from many neurons from many birds. Through this method, they found that there were non-selective neurons that responded to all the songs, but also selective neurons that had a very selective, and in many cases, exclusive, response to the tutor songs.

“In the normal, tutored birds, we encountered a group of neurons that responded very strongly to the tutor song, after they had learned the song, but did not respond to the other songs,” Yanagihara said. “However, for the birds which had no tutor experiences, we did not see any response to the tutor-song, or in this case the genetic-father-song, and no selective neurons at all.”

The team found that approximately five percent of the neurons in the higher auditory cortex reacted to the tutor song and that this could be indicative of where the early auditory memory is located in the brain.

“We found 27 neurons that selectively respond to the tutor song,” Yanagihara said. “We believe that these tutor song selective neurons represent the memory of the tutor song and that learning the tutor song during the critical period changes the neural circuits to accommodate this memory.”

This is important because the brain mechanisms during the critical period are still not very well understood. These findings could be a step in grasping how the brain circuit is shaped during this early stage development and how these neuronal circuits contribute to higher cognitive function in adulthood.

“This study gives some idea of how the brain acquires memories during the critical period,” Yanagihara said. “This is a step in understanding how the neuronal mechanisms of memory and early sensory experiences form brain circuits in the early developmental stage, not only in birds, but also in humans and other species.”

Specialty

Research Unit

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form