New Theory of Okinawan Coral Migration and Diversity Proposed

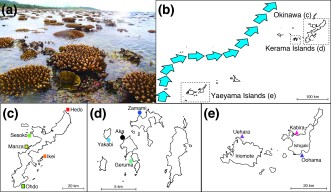

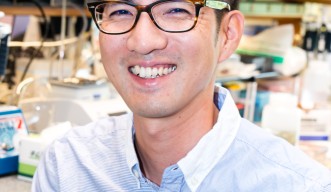

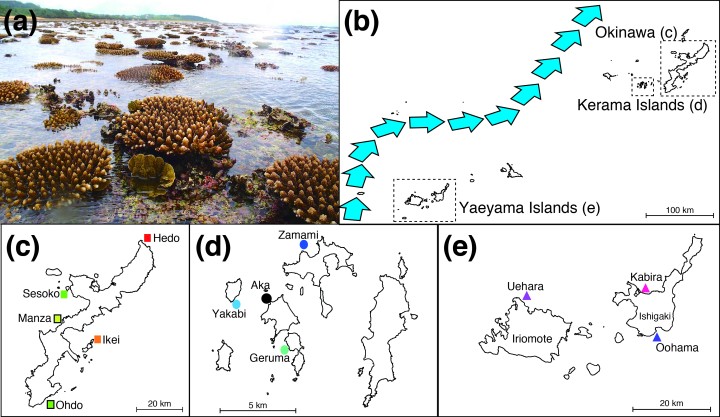

A team from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), led by Group Leader Chuya Shinzato in Professor Noriyuki Satoh’s Marine Genomics Unit, has analyzed the genome of 155 samples of Acropora digitifera corals and proposed a new theory on how coral populations have migrated within the Ryukyu Archipelago, in southern Japan. Their findings have just been published in Scientific Reports.

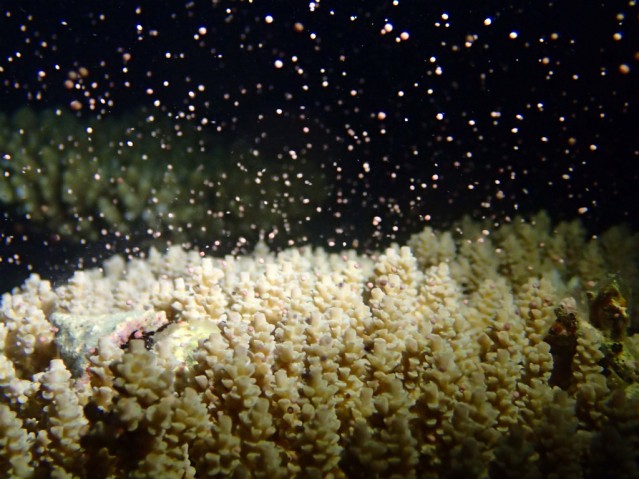

Full moon nights in summer are very special for corals. At 10 p.m., when water is around 24°C (75°F), Acropora digitifera corals in the southernmost part of Japan start to release their eggs and sperm, known as gametes, exactly at the same time in a process called synchronized spawning. Since corals cannot move to find a partner, they let their reproductive cells free float in the ocean, hoping for an encounter. Understanding how the resulting newborn coral larvae migrate and settle is crucial to protect our beautiful coral reef.

One of the most outstanding and diverse coral reefs in the world is found in the Ryukyu Archipelago, a group of subtropical islands and islets belonging to Japan and blessed by the warm Kuroshio ocean current. In 1998, a worldwide coral bleaching event destroyed the corals in some parts of the Archipelago. It seriously damaged the corals in waters around the Okinawa Islands, but did not affect the ones in the Kerama Islands. It took a decade for the some corals of the Okinawa Islands to recover and the common belief was that the Okinawa corals repopulated thanks to the dispersal of healthy coral larvae from the Kerama Islands, which are 40 km away. Coral genome analysis conducted by OIST has now showed that this is very unlikely.

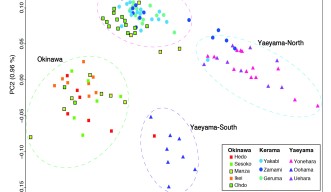

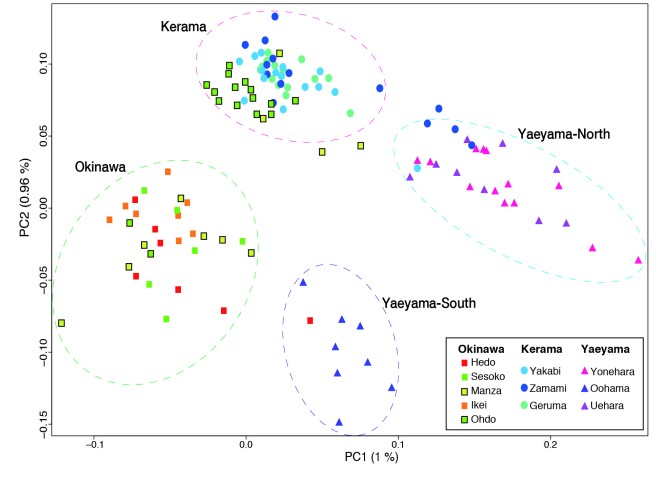

OIST scientists analyzed the genome of 155 samples of Acropora digitifera corals, collected across the Ryukyu Archipelago. In particular, they focused on subtle genetic variations that can be used to differentiate these corals into subpopulations. OIST scientists took into account 905,561 of these variations, called single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs, pronounced “snips”. The genome analysis showed that the corals divide into 4 groups, corresponding to their geographical distribution: the Okinawa Islands, the Kerama Islands, the Yaeyama-North and the Yaeyama-South. This result has significant implications regarding the recovery from the 1998 coral bleaching. “If the corals in the Okinawa Islands were repopulated thanks to migration of coral larvae from the Keramas, we would expect to see the genetic clusters of Okinawa Islands and Kerama Islands merging together. Instead these clusters are very distinct,” explains Dr Chuya Shinzato, first author of this study and active member of the Coral Reef Conservation and Restoration Project spearheaded by the Okinawa Prefecture. “This result shows that the coral populations of the Okinawa and Kerama Islands have not met recently. It means that long-distant larvae migration by spawning within the Ryukyu Archipelago is less common than what was previously thought.” It is therefore more likely that the survivors of the 1998 bleaching in the Okinawa Islands repopulated themselves, without mixing with the corals from the Kerama Islands.

Well-known for the richness of their corals, the Kerama Islands won the status of a Japanese national park in 2014. The Keramas were believed to be the point of origin of coral migratory pathways in the Ryukyu Archipelago. However, OIST researchers have discovered that these Islands are sinks of coral migration, rather than sources. Their “melting pot” explains the abundance and diversity of the Keramas’ corals. On the other hand, in the case of another disruptive event, such as coral bleaching, the Keramas’ corals cannot guarantee the recovery of the affected areas. “We need to protect coral reefs locally all over the Ryukyu Archipelago,” points out Dr Shinzato.

Coral populations are under threat across the globe. The analysis of coral genomes in relation to their larvae migratory pathways is essential to preserve and restore the richness and beauty of the coral reef.

Specialties

Research Unit

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form