Fly spit yields find about genetic controls and differences between sexes

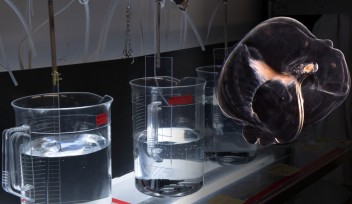

We all know someone whose curiosity about how things work has led them to dismantle their computer, phone, or TV. But there is probably only one person in the world who has dissected 10,000 fruit fly larvae to find out how they work. That person is Thomas Conrad, a graduate student with Prof. Asifa Akhtar at the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Germany, and fortunately his efforts to extract the larvae’s saliva glands, along with the extensive analyses that followed, paid off. In a paper published yesterday in Science, Conrad and his collaborators, including OIST Adjunct Assistant Professor Nick Luscombe, show that the long-accepted view of how male fruit flies manipulate their genes’ activity should be revised. Their finding shows how cells use a single, crucial regulator to change the activity of large numbers of genes at the same time.

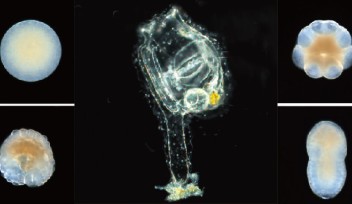

The larvae, and Conrad’s time, were sacrificed to answer a sticky question about the differences between male and female flies, and about genetic regulation more generally. As in other animals, male flies have one X and one Y chromosome, while females have two X chromosomes, so the genes on these chromosomes need to be regulated to keep females from having twice as many proteins from X-chromosome genes as males do. Flies solve this problem by having the male X-chromosome genes work double-time, producing twice as many proteins so that the males can keep up with females.

But this is a more difficult feat than it sounds, since each of the genes produces a different amount of protein. “It’s like you have 1000 half-filled glasses of water that you want filled. But because the glasses are all different sizes, this mechanism must somehow ensure that each glass gets different amounts of water to achieve this,” explains Prof. Luscombe. The regulation occurs when genes are switched on, or transcribed, which is one of the first steps toward making a protein. The commonly-held view was that transcription is equally likely to begin on male and female X-chromosome genes, but that for some reason it is more likely to run to completion on the male genes. But after the Max Planck Institute researchers chemically analyzed the DNA strands in thousands of fly spit glands, and Florence Cavalli and Juanma Vaquerizas in Prof. Luscombe’s group at the EMBL-European Bioinformatics Institute crunched the data using sophisticated computer algorithms, they were surprised to find twice as many of a DNA-transcribing protein attached already at the start of genes in male flies than to the female version. This means the difference between males and females is rooted in the beginning of the transcription process, when the protein first binds to the DNA, rather than the end, as had been thought.

Whatever strange mechanism ultimately explains the ability of X-chromosome genes to do double duty is likely to have implications that go far beyond fly spit. Says Prof. Luscombe, “We’re looking forward to finding out more about what makes this kind of mass regulation possible, and how it fits in with other means cells have of fine-tuning their use of genetic information.”

Research Unit

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form