New Unit Profile: Knocking Out Pathogens

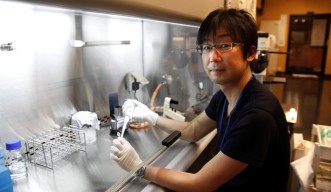

Having spent a good portion of his post-doc career at the University of Miami (UM) in Florida, USA and loving the warm weather, it wasn’t too difficult to sway up-and-coming immunologist Hiroki Ishikawa to take a position in Okinawa at OIST. But blue skies and ocean breezes weren’t the only thing that drew him to the university. “OIST strongly encourages interdisciplinary work, which was a very attractive feature to working here over other institutions,” says Professor Ishikawa, head of the new Immune Signal Unit at OIST. “I’m excited to take advantage of opportunities to work with researchers outside of my field.”

Having only been a part of OIST for two months, Ishikawa is still building up his lab. In the middle of November a technician from Okinawa will join the group and in January Ishikawa also expects the arrival of a post-doc from Europe. Though he's already made a number of substantial accomplishments in his career, Ishikawa is only 35 years old. “As a young scientist in Japan, it’s very difficult to find a position as an independent researcher with one’s own lab at my age,” he says. “Generally, one has to work under a senior professor for a long time before these kinds of opportunities become available.”

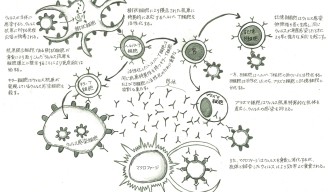

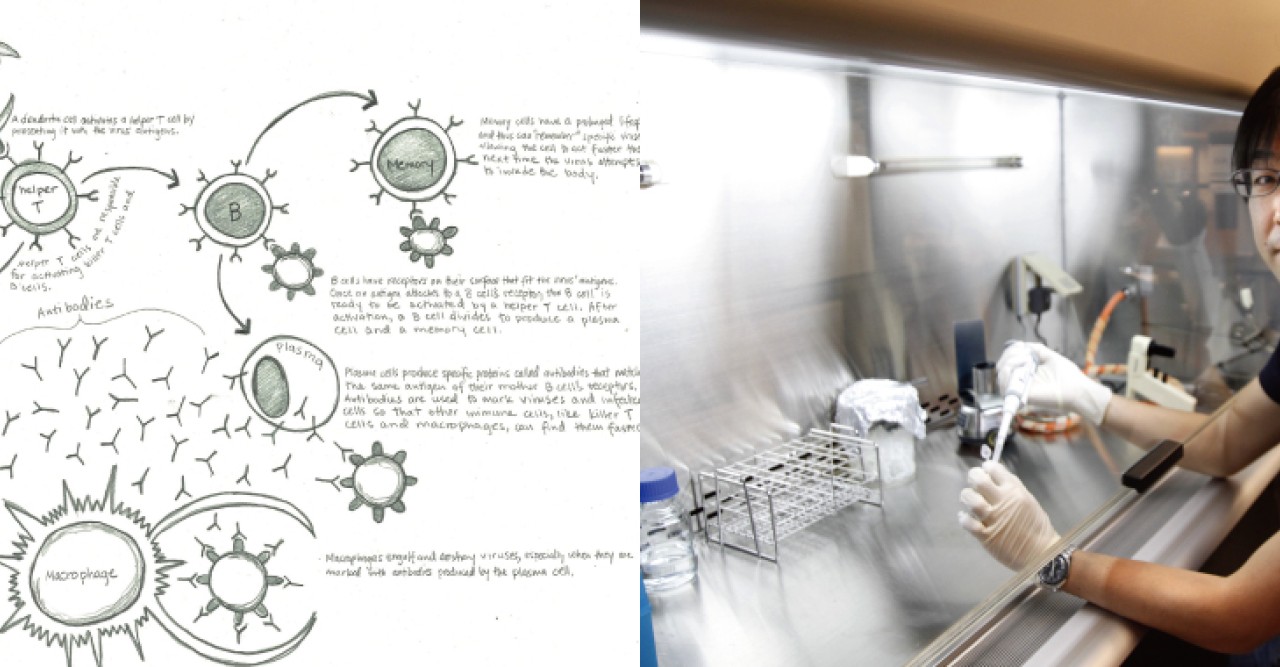

As an immunologist, Ishikawa studies how our bodies defend themselves against pathogens like bacteria, fungi, and viruses using the mouse as a model. All animals and plants have some form of innate, or non-specific, immune system, an organism’s first and immediate weapon against infection or disease. This system is considered evolutionarily older than the adaptive immune system, a more specialized defense that researchers believe evolved in the first jawed vertebrates over 450 million years ago.

Unlike the innate immune system, cells in the adaptive immune system can recognize and remember pathogens the organism has been exposed to previously. The adaptive immune cells’ superb memory allows the animal or plant to form an immunity to some illnesses for life. Thanks to the adaptive immune system, for example, most people don’t get the chicken pox (varicella virus) more than once, and with the development of the varicella vaccine, they most likely will never get it. The whole premise behind a vaccine is to expose an organism to a small amount of a pathogen so that its adaptive immune cells learn how to organize powerful attacks for future, stronger infections. The innate system always responds to pathogens first and this subsequently activates the adaptive system. Only working as a pair can they defend the body successfully.

At the University of Miami, Ishikawa, together with his mentor Dr. Glen Barber, made an important discovery in the molecular basis of the innate immune system that landed them two publications in Nature, one in 2008 and another in 2009. Using a genetically engineered mouse that researchers have dubbed the ‘knockout’ mouse because one gene in the animal’s genome is turned off, Ishikawa and Barber identified STING (stimulator of interferon genes), an important gene that regulates how immune cells respond to the presence of a bacteria and DNA viruses, such as the Herpes virus. The researchers found that with STING turned off, the entire innate immune system of the knockout mice couldn’t defend themselves against these pathogens – leaving the animals lethally susceptible to even the weakest infections.

At OIST Ishikawa has turned his attention to understanding how exactly the adaptive immune system is activated by the innate system. He also wants to work on how immune cells in the adaptive system form their memories of pathogens. His research aims to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the immune system in order to design more and better vaccines that provide individuals with long-lasting protection from pathogens.

Specialties

Research Unit

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form