[Column] Coincidence and Curiosity Lead Researcher to Typhoon Research from New Angle

The latest OIST column in the Asahi Shimbun GLOBE+ is out now! This month, OIST Media Relations Section manager, Tomomi Okubo introduces Prof. Pinaki Chakraborty because she believes that he is one of the best examples to explain what "curiosity-driven research" means.

Coincidence and Curiosity Lead Researcher to Typhoon Research from New Angle

When in doubt, follow your curiosity... the teachings of Nobel laureates

At a press conference held the day after the announcement of Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine last year, an Okinawan reporter asked Prof. Svante Pääbo of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), "Do you have any message to the young people in Okinawa?"

His answer left a deep impression.

"If you are wondering or not sure about what you should do in life, I suggest that you should do what you are interested in because you tend to do it well. And if you are lucky, it will become your profession and you will be able to make a great contribution to the world. Follow your interests and don't be afraid to take on challenge."

Similarly, Dr. Shukuro Manabe, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics, emphasized the importance of following curiosity many times.

Media reported that Dr. Manabe used the word "curiosity" several times at the press conference held at Princeton University in the U.S., such as "I think most interesting research is driven from curiosity" and "What drove me was pure curiosity." He expressed a concern about the research environment in Japan, saying that the researchers are engaging in "less and less curiosity-driven research."

Competition for Research Funding: Endless Loop of Grant Application

Behind this remark is the ongoing reality in the world of scientific research.

Research in general requires money, whether small amount or large, for various things including equipment, supplies, and human resources for the research, registration fees and travel expenses to attend the conferences that would contribute to the research, and to write and publish papers in scientific journals.

University faculty members need to continuously obtain research funding to maintain their laboratories, because the budget allotment from the university or research institution is often not enough to conduct continuous research.

Japan has an official system for competitive research funding. The funding agencies such as Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) under the government organizations such as the Cabinet Office, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), provide subsidies to various research programs, including "Project for Promotion of Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-PROMOTE)," "Advancement of Hydrogen Technologies and Utilization Project," and others. Researchers apply for these grant programs to obtain funding for the research they wish to pursue by submitting research proposals.

Some grant programs that offer larger funding become more competitive, making the chances of not receiving the fund higher for the researchers. As you can imagine, this puts the researchers in a situation where they have to set their research goals in line with the program objectives and conduct the research according to the plans described on their grant applications. In addition, the researchers are expected to achieve the research goals within the timeframe specified by the programs (often a few years).

Furthermore, researchers find themselves stuck in a never-ending loop of grant application, cycling through these grants, spending more time preparing grant applications than on their research.

Career Led by Curiosity and Coincidence, Transition from Mechanical Engineering to Theory and Geology

OIST was established as a new research and educational institution to create a truly innovative and outstanding research institution in Japan. Therefore, the university has an environment that allows outstanding researchers with creative ideas to pursue innovative research, without getting stuck in the swamp of grant application.

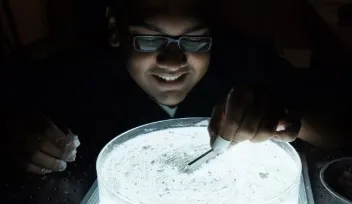

Professor Pinaki Chakraborty, 43, is the perfect example of what curiosity-driven researchers may look like.

Professor Chakraborty arrived at OIST in 2011, the same year OIST was founded.

He leads a research unit called the Fluid Mechanics Unit, which studies the "flow" of all kinds of materials using theory, experiment, and simulation. He and his team have conducted curiosity-driven research on a variety of subjects, including the flow of oil and gas in pipelines, the formation of the radial traces around craters on the moon, the mysterious surface of the asteroid "Itokawa," and the relationship between climate change and typhoons.

As a child, Professor Chakraborty had no interest in studying and spent most of his time playing. However, in high school, he met an elderly physicist, who greatly changed his life.

Although he had no interest in schoolwork but realized that he liked "understanding things" from listening to the scholar about classical physics. From then on, young Chakraborty looked up to this scholar as a mentor and started going to his house after school. The physicist taught him mechanics, and young Chakraborty became fascinated with it.

In the university in India, Chakraborty majored in mechanical engineering, thinking that he would be able to learn about mechanics. However, as he was interested in understanding things, he thought that the application-oriented mechanical engineering was not for him. He wanted to simply pursue his study to understand things, so he decided to go to graduate school in the United States. He happened to discover that he could study theoretical and applied mechanics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and earned his master's degree and doctorate.

Young Chakraborty was studying theoretical and applied mechanics, but when his colleague geology professor asked him questions about the shapes of volcanic plumes, he decided to collaborate with the geologist. After finishing his doctorate program, Dr. Chakraborty joined the geology department as a post-doctoral fellow.

The laboratory was led by Prof. Susan Kieffer, a MacArthur fellow (the grant is also known as the “genius grant”) and a member of the National Academy of Sciences with abundant research funding. Therefore, Dr. Chakraborty felt privileged as a post-doctoral researcher to be able to do curiosity-driven research the way he liked.

His wheel of fortune showed no sign of stopping.

His paper on volcanic plumes published in the scientific journal Nature happened to catch the eye of Dr. Roscoe G. Jackson II,a graduate of the Department of Geology at the Illinoi University who had become a wealthy business man through his family’s business. Dr. Chakraborty got the fellowship established at the university through the donation of this person. Chakraborty, again, was able to pursue his curiosity-driven research independently without anyone dictating his research.

Traditional and Prominent, or New University? Choosing OIST Despite Risks

Although Chakraborty enjoyed the privilege of having the freedom of research, he also wanted to become a professor to advance his research career.

He applied to various universities with a number of offers but was not sure what to do as none of them seemed more appealing to him than the environment he was in. Then one day, someone forwarded him an e-mail saying, "Pinaki, maybe you will like this place."

It was an e-mail from the then-president of OIST notifying that they were looking for researchers to work at the university. Chakraborty had a good impression of Japan but was skeptical about whether he would really be able to have the freedom of research in Japan. Anyway, he decided to go for the interview out of curiosity.

Then, fate plays its tricks on him again.

After he arrived at the airport to go to his interview, his flight was canceled due to a snowstorm. He almost gave up on the idea of going to the interview, but then the blizzard stopped three days later. The flight and interview were rescheduled smoothly, and he was on a plane a few days later. After leaving the university town of Illinois surrounded by the flat silvery cornfields, Dr. Chakraborty landed in Okinawa, a beautiful paradise surrounded by blooming flowers and blue seas, and he fell completely in love with the place.

His concerns about the research environment were resolved at the interview, in which a prominent researcher of high-energy physics, Dr. Jonathan Dorfan, who was the President of OIST at the time, explained to him about OIST's philosophy and direction. Listening to Dr. Dorfan, Dr. Chakraborty was convinced that this university had future.

While Dr. Chakraborty received an offer from OIST, he received another offer from a prominent university where he had previously interviewed.

It was a tough decision for Dr. Chakraborty because the other offer was from a prestigious university with a long history, and everyone admired it. People recommended him to choose the prestigious university because it was a large institution that had an environment in which researchers could conduct research with many other excellent researchers.

However, Professor Chakraborty had an opposite view. He thought the geographical isolation of Okinawa was ideal.

He thought it would allow him to really get down to his own ideas without being influenced by other people’s opinions and minimize the possibility of some prominent researcher crushing his interest and ideas by saying, “That is a waste of time.”

Professor Chakraborty says, "There may be risky to do research that no one is interested in. But if you like risks and are willing to take on challenge, OIST is the perfect place for you, though it may not be for everyone."

Looking at "Typhoons after Landfall": Bringing New Perspectives and Research Results to the Field Outside of Specialty

Dr. Shukuro Manabe, who was mentioned in the beginning of this article, received the Nobel Prize for research that showed how increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere lead to increased temperatures at the surface of the Earth, the concept widely known today. Dr. Manabe said, "I never imagined that this thing I was beginning to study [would have] such huge consequences. Curiosity is the thing which drives all my research activity. I believe that major discoveries that have a great impact later are those that no one realizes the importance of their contribution at first". (Quoted from Asahi Shimbun, Nobel Laureate in Physics, Dr. Manabe, "I enjoy studying climate," "Curiosity is the driving force,")

Prof. Chakraborty’s typhoon research that he worked on with his student (at the time), Lin Li, was also driven by the student’s curiosity. Neither of them had any background in the study of typhoons or meteorology. However, they felt that "there has to be some interesting forces at work there. Many researchers in this field are interested in typhoons at sea, but Prof. Chakraborty and Li focused on typhoons after they made landfall.

Prof. Chakraborty said they were able to look at the problem from a new angle because they came from completely different background.

Typhoons contain plenty of moisture collected from the ocean surface as it crosses the ocean. The moisture acts as a fuel for the typhoon engine and drives its intense winds. Once they make landfall, they can no longer increase their intencity due to lack of moisture from the ocean. In addition, they lose their intencity as they rub against the complex terrain on land. However, Li and Chakraborty showed that the moisture that is stored in a typhoon from its journey over ocean prior to landfall still fuels its intensity. Further, as the ocean temperatures rise with global warming, typhoons will store more moisture. This additional moisture will fuel their intensity for longer as they move further inland.

Prof. Chakraborty and Li analyzed data on hurricanes that have made landfall in the United States over the past 50 years and determined that there is a correlation between sea surface temperature and the level of inland penetration by typhoons. Their findings were published in the scientific journal Nature and widely covered by media around the world. In the future, this research may lead to the prediction of typhoon intensity and disaster prevention and may even be used in areas we do not expect.

In summarizing his experience, Prof. Chakraborty noted “although my abilities are rather mediocre, I have been very lucky to work with very talented people and to be in an environment that nurtures curiosity-driven research. Whatever little I have been able to do, I owe it to this potent mix.”

(You can read more about this study here: Climate change causes landfalling hurricanes to stay stronger for longer)

----

Written by Tomomi Okubo, Manager of Media Relations Section, Public Relations Division, OIST

Pinaki Chakraborty

Prof. Chakraborty, head of the Fluid Mechanics Unit at OIST, was born in India and graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology, Surat (SVNIT Srat). After receiving his master’s degree and doctorate (Theoretical & Applied Mechanics) from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the U.S., he worked as a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Geology at the university and continued his research as Roscoe G. Jackson II Research Fellow. He has been a professor at OIST since 2011 (initially as an adjunct professor and became a full-time professor in 2012).

Specialties