Tiny atoll in the Pacific Ocean offers glimpse into warmer world

To an outsider, Taiaro Atoll is a golden, palm tree covered, coral ringed paradise. But this tiny stretch of land, just 5km in diameter, also acts as a boundary that could help scientists answer questions about evolution and the future of our ocean. Located in a remote corner of French Polynesia, a 12-hour boat ride from the nearest airport, the atoll completely surrounds a lagoon—one that is both warmer and saltier than the surrounding ocean.

“Previous scientific expeditions to this atoll occurred in 1972, 1994, and 2006,” said Prof. Vincent Laudet, Principal Investigator of the Marine Eco-Evo-Devo Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST). “And, remarkably, these expeditions identified 125 species of fish living in the lagoon.”

But this finding brought up more questions than answers: Do the fish live out their entire lifecycle within the lagoon or are they carried in on exceptionally high waves? Are they genetically distinct from their oceanic cousins? And how have they adapted to the warmer and saltier conditions?

So, in October last year, Prof. Laudet and a team of 11 other scientists set out to answer some of these questions. The journey took him, and OIST Postdoctoral Researcher Dr. Marcela Herrera Sarrias, from Japan to Hawai’i to Tahiti and then to Fakarava where they boarded boat for the 12-hour journey to Taiaro Atoll. They were joined by scientists from the Center of Island Research and Environmental Observatory and other institutes in France.

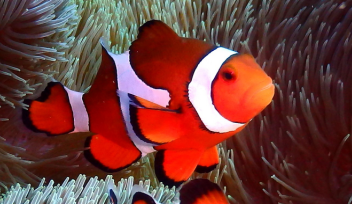

But the research was by no means easy. After negotiating waves and coral to reach the shore, all while carrying essential items like scientific equipment and a freezer, the researchers constructed a basic camp on the beach. A molecular biology lab was set up on a foldable table, beneath a tarp. The freezer, which was used to store any samples, was taken to the house of the only inhabitants of the atoll, some 3km away from the camp. Everyday Dr. Herrera Sarrias made the 6km return journey on foot or bike to store her samples. She was specifically looking at whether the fish within the lagoon had different genetics to the ones outside the lagoon. To do this, she focused on several species of fish including convict surgeonfish and butterflyfish.

“These two species had been studied by the previous expeditions,” explained Dr. Herrera Sarrias. “The convict surgeonfish especially is a model organism for eco-physiological studies on reef fish, and we have the full chromosome-scale genome. We collected the fish from inside and outside the lagoon with the plan to compare the genomes and find out what molecular adaptations might exist to allow the fish to thrive in such warm and salty environments.”

With the basic molecular biology lab onsite, Dr. Herrera Sarrias spent much of her ten days on the atoll dissecting fish. As well as extracting samples for genome analyses, photos were taken of the fish, alongside organs, to see if there were any noticeable differences between the fish in the lagoon and the ones in the ocean. She also collected the ear bones to check for chemical differences. Once the dissection was complete, she made the 3km journey to the house to store all the samples.

Other scientists set up buoys to in the ocean and the lagoon and cameras on the southern edge of the atoll. Their theory is that in June and July, when there were large waves coming from the south, water that potentially was carrying larvae or small fish would enter from the ocean. The buoys are now sending hourly information, via satellite, to OIST on temperature, salinity, phytoplankton, and water level.

There was also a chemist who looked at the makeup of the lagoons water and whether it would promote the growth of algae. She found that the water inside the lagoon was of poor quality, which only added the question, what do the fish eat?

Finally, biologists were looking for fish larvae. “Larvae are very difficult to find in the open ocean because it’s so vast and they’re so tiny,” said Prof. Laudet. “But the lagoon is much smaller. If the fish live out their entire lives in the lagoon, they must be there.”

But the biologists didn’t find larvae or any plankton. Instead, they found thousands of small needlefish and jellyfish. Prof. Laudet noted that there was also a large array of predators—barracuda, stone fishes, grouper, and moray eels—right at the spot where they expect large waves might be able to enter the lagoon.

The mysteries of the lagoon, and how such a rich community of fishes seems to thrive in such poor conditions, will take time to answer. For now, the scientists are analyzing their results, watching the cameras, and observing the temperature and salinity. Some of the scientists wish to return to the atoll in April. If they find juvenile fish, then Prof. Laudet has one answer—larvae must exist within the lagoon, as no large waves can be expected before June. And these larvae, and thus the adult fish, have somehow adapted to living in these conditions, which might well be the conditions of the future.

Cover image by Pascal Kobeh.

Research Unit

For press enquiries:

Press Inquiry Form